|

IN PRACTICE

|

|

A SUSTAINED EXPERIENCE OF COMMUNITY PLANNING IN LA HABANA, CUBA°

|

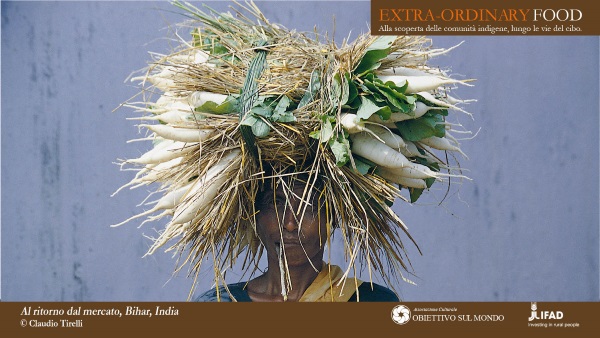

Rosa Oliveras Gómez * The capital city La Habana (Havana) has a long history of central importance to the Cuban economy. Before 1959, La Habana hosted 25% of the national population and concentrated more than three quarters of the country's exports, half of its marketable services, 60% of the imports and 41% of the hospital beds, as well as almost all of the research centres As a consequence of the low level of development in the rest of the country at the triumph of the revolution, it was inevitable and imperative that attention be paid to development in other regions of the country. The result was a series of production and service investments towards provincial capital cities and other intermediate cities. This process partially decreased the enormous distance between the capital and the rest of the national territory. However, very limited material and financial resources neither supported the development of La Habana, the rehabilitation of its buildings, the reduction of inequalities between central and peripheral areas of the city in terms of services and infrastructures, nor dealt with the problems associated with its internal migration, even though this is relatively modest. This resulted in a concentration of physical, economic and social problems in the capital. La Habana's high population of 2 million inhabitants, its unequal distribution of population and economic services, its historical growth over 490 years, and its three different socio-political systems have all contributed to the creation of a diverse and segregated city, yet with highly valuable assets. A great variety of necessities and local vocations emerged that have made it complex to develop a city that would reflect many visions and provide access and opportunities to all its residents - all while restoring La Habana's role as the "Key to the New World" and "Pearl of the Caribbean". The population of La Habana inhabits diverse spaces within the city. A densely populated and compact area, known as "traditional Havana", with a population density of 1000 inhabitants per hectare is characterized by overcrowding, an abundance of walls, a lack of public and green spaces, toilets at every street corner, and strong interpersonal and functional relations. A great sense of belonging to the neighbourhood, traditions and several generations of families living in the same houses are contributing factors to social cohesion. Similar to other inner cities, the poverty level has increased and the invaluable built heritage has fallen into such disrepair that it practically impossible to recuperate. The city's periphery, on the other hand, is sparsely populated, discontinuous and poorly connected. Not having always been part of the municipality, many services available to those living in central Havana are not available to those in the suburbs. Between "Old Havana" and these suburban areas lies another urban zone that shares several characteristics of both. These features demonstrate how diverse kinds of urban spaces colour the ways of life, behaviours, and interpersonal communication styles within a community, all influenced by the type of urbanization pursued in the 65 traditional barrios and 328 new residential areas (repartos), mainly created in the first half of the twentieth century. Recent context The degree of centralization in Cuba has increased or decreased over the 50 years since the revolution, depending on the economic situation, the American embargo, and the political context at different times. The central State's vertical decision-making process has involved every sphere of policy making and implementation; and while the social policies generated have responded to verified needs that were national in scope, they did not always take into account local characteristics and priorities. Social organizations created in the neighbourhoods in the early 60's were a reflection of the structures and goals that had emerged. The most representative organizations included the Committees in Defense of the Revolution, which carried out surveillance and undertook other tasks, and the Federation of Cuban Women, which promoted women's development and their inclusion in social life. Through community engagement, these organizations undertook tasks with a social benefit, such as vaccination campaigns. Although managing to massively mobilize the population, the main objective was to implement tasks that had already been defined, and so meaningful participation of the community in decision-making processes was rare. In 1976, Popular Power (Poder Popolar) 1 was created to bring the government closer to the people. It was organized at the grassroots level through representation, by delegates from circumscriptions of approximately 1400 inhabitants each. This structure and the administrative subdivision2 of the country into new provinces and municipalities facilitated the development of the territory, increasing the number of focal areas for development. Nevertheless, these levels have very few financial resources. This is because all investments, reparations and equipment are directed to the local territories through national Ministries. As a result, all financial resources flow from the top to the other levels of government in a vertical and sector specific way, leaving very few resources available for municipal governments. The dominant idea that the State itself would be capable of meeting the entire national demand meant that the economy was reliant on big enterprises dispersed throughout the national territory that would supply all the country's needs. Both technology and production were resourced accordingly, and no room was left for the development of small and medium enterprises that could address regional, provincial or municipal demands, create jobs and reduce inputs, the need for transportation and save time. There was no law that would allow municipalities to create small enterprises or service establishments, as these were the rerogative of the national government. Current legislation uniquely supports individuals working on their own in limited economic activities, and does not cover cooperative production while it also restricts the participation of family members in any of the permitted economic activities. The State has been the only provider of goods and services to both municipal and provincial bodies, and the population in general. This has generated a passive attitude towards possible solutions and initiatives, resulting in limited horizontal institutional collaboration, a sectoral approach, the reinforcement of hierarchical decision-making processes, and room for arbitrary decisions. Several years after establishing Popular Power, the Popular Councils3 were created in 1990 as an intermediate level of government between the local delegates and the Municipal Assembly, to facilitate a better understanding of and draw attention to the needs and interests of the local communities (approximately 20,000 people each). Subdivision delegates and their president are elected every two and a half years. Because turnover in representatives is high (60%) there is a need to ensure some continuity in the work with grassroots groups, especially those actions concerning the future. The most dramatic crisis of the Cuban economy, known as the "Special Period in Time of Peace", came at the beginning of the 1990's with the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Eastern Block. At that time commercial exchange was drastically reduced to 15%. A shortage of raw materials and electricity followed. As a result it was deemed necessary to reduce working hours, close industrial facilities and take urgent measures to survive. Many more people kept to their own neighbourhoods because they had lost their jobs and public transport was reduced. The barrio became a place where people tried to resolve their economic, cultural, and recreational needs. This implied that solutions to the problems people faced could be created through community participation and mobilizing local resources. As part of the measures to mitigate the effects of the Special Period, in 1994 the number of activities that could be registered as self-employed was increased to over 100, although with the same limitations. In spite of the increase in the licenses issued and a significant increase in the number of self-employed people, there remained no viable system to supply raw materials, financing for production and services or for commercialization of products, and with time, businesses started to languish. Nevertheless, as the economic crisis diminished, local potential was dismissed in favour of a traditional centralized solution, and without the creation of a legal framework, a budgetary redistribution or a systemic reorganization that could allow local governments greater participation in their own development. An institution to rescue and develop the city Given the urgent need to turn attention to the city, in the 80's a series of investment programs were promoted, together with actions to resolve Cuba's long-standing debt. This plan required policies and objectives for urban development that would provide guidelines for how to improve living conditions for the people in La Habana. In order to facilitate the city's liveability and advise the provincial government, in 1987 the Group for Integral Development of the Capital (Grupo para el Desarrollo Integral de la Capital - GDIC) was created with the mission of promoting development that would be sustainable, participatory, economically viable, socially just and ecologically favourable for La Habana. Among other strategic objectives, the Group gave impulse to a new creative, participatory and decentralized focus that considered the barrio as the most human urban element in which citizens shape their sense of belonging. In this way, the proposal for the city's development would be sustainable, starting from the commitment and the genuine identification of the inhabitants with their neighbourhoods, while working on satisfying needs and priorities at both the grassroots and the city level. Given that the contemporary concept of development has become more tied to the local level, to strengthening the most important tangible and intangible heritage, and also the awareness that cities should be for people - the individual and the community - as the beneficiary of improvements, it was possible to give proper emphasis to the priorities of development: people rather than material objects. In 1988, under a proposal by the GDIC, three small technical teams were created to promote the transformation of the barrio, through active and engaged participation of its institutions, residents and organizations. The first three Integral Barrio Transformation Laboratories (Taller de Transformación Integral del Barrio - TTIB) were established - two in the central area and one in the periphery. These three were the only talleres (a sort of participatory action research process- translator's note) selected at the community level to be tested for their relevance and viability. Other talleres were requested by the municipal governments and the Popular Councils in areas characterized by difficult liveability conditions and related social problems. The contribution recognized by the institutions stimulated the creation of new talleres, now 20, distributed in 9 of the 15 municipalities within the city. Each taller is assigned a population of 500,000 inhabitants. Technical teams for community development: the Integral Neighborhood Transformation Laboratories Technical and multidisciplinary teams are composed of 3 to 7 professionals whose expertise originally ranged from the psychological and pedagogical spheres to social assistance. Other areas of professional expertise were later incorporated in order to better respond to the diverse needs in each community without necessarily increasing the number of professionals. By limiting the number of staff in the working teams, the TTIB did not take on work that fell within the jurisdiction of existing institutions or organizations, therefore facilitating coordination with these latter and the integration of work horizontally. In order to assure maximum effectiveness in their work, TTIB's staff are required to comply with a series of requirements:

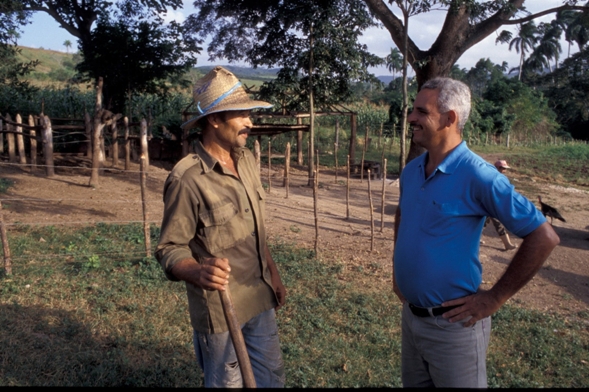

Through their commitment to uniting institutional and community participation, the TTIB have become catalysts for many actions. Drawing from local resources, they exercise the dual function of promoting and researching feasible solutions, while satisfying the needs of individuals and communities that are involved and consulted. This focus on city development and diversity, or the appropriation and shaping of urban space according to the residents' ways of life, has been the comprehensive mission of the TTIB for 20 years. The "comprehensive" approach includes multiple perspectives, both present and future, and combines various disciplines, while at the same time aiming to develop solutions that respond as closely as possible to physical and social needs. This is one of the elements that has enabled urban development to take place: just as in a living organism, every part of the city belongs to its communities and every community belongs to the city as a whole. The Popular Council's mission in the communities was facilitated through the technical teams and in practice, the TTIB became part of the Council itself. Thanks to stability and capacity, the TTIB ensured the continuation of action towards strategic community development objectives, even during political changes. TTIB's Work Style Systematic and face-to-face interaction with the local people, institutions organizations, as well as with government, characterizes the daily work of the TTIB. Each TTIB works with grassroots and formal leaders, who are stimulated and integrated in the conversation, to ensure a stable line of communication between the community and its representatives. Its members are trained in the Popular Education4 school of thought, that allows them to have a different, more stimulating and tolerant approach towards everyone, whether it be people or institutions. It also creates an environment for more effective educational work in the barrios, in that education becomes an exchange of knowledge rather than just passive absorption. Another fundamental principle for enhancing the involvement of different groups in the community was building capacity both within the teams themselves and within the local governments. Training was designed and delivered to respond to a Capacity Building5 strategy, intended as "the ability to realize and achieve proposed actions for community transformation and to make it possible for every participant to play a role that is effectively, efficiently and sustainably suitable for them". This strategy was co-produced by the GDIC, as a methodological advisor, and representatives from each of the Talleres, with the purpose of understanding the reasons, timing and content of the trainings and, especially, of finding out what content would match the needs defined by the communities6. As part of this strategy, it was also established that the trainings be carried out to create grassroots multiplier agents who would pass on their acquired knowledge to others, with a ripple effect. Fundamentally, the GDIC imparts and coordinates the sharing of information among TTIB teams and government members through specialized centres. They then pass this information on to representatives of institutions and grassroots organizations and leaders. They appeal to the sentiment of community among the residents to increase their involvement in barrio regeneration process Cultural, recreational and sport activities, designed with an educational lens and targeting different groups, have been the most effective way to create a connection with the community. Targeted groups are comprised of children, youth, women and elderly people. The activities are animated by neighbourhood leaders, who constantly work to support these groups in consolidating the traditions and artistic manifestations of the neighbourhood. Eighteen Community Centres, created by the community members, have become crucial spaces where the work is carried out, as they are also home to various other community and public activities.

Children from Buena Vista learning to improve their neighbourhood environment Primary functions Aligned with their mission, the TTIB started developing a series of functions that evolved according to new opportunities or threats presented to the city and the country at specific moments in time. Among others, priorities included supporting decentralization with concrete actions, and identifying and supporting the contribution of each barrio to the city, in order to obtain a more equitable development for all its citizens while strengthening and preparing its human capital. These functions point to paths capable of responding to demands and needs from the population while transforming its consumerist attitudes; activating horizontal relations through common objectives; understanding and communicating with each other through a common language; and giving the community the strength to transform and re-organize its own neighbourhood. For these reasons, the TTIB works to:

In order to preserve La Habana and its rich and diverse identity, efforts have been put into place to maintain the heterogeneity of its various neighbourhoods, and to strengthen the feeling of belonging that stimulates participation in the community. One of the results has been the creation and publication of 18 local histories, addressed not only to residents but also to elementary schools, libraries and other institutions. TTIB discusses, produces and implements actions together with the Social Prevention Commissions7, as an indispensable part of human improvement in the communities, where, due to greater proximity, there is a better understanding and empathy for people in need. It is in this context that workshops were developed for single mothers, elderly people without family network, former inmates and their relatives, children and youth out of school, prostitutes and pimps, and other actors. Many of these workshops were designed to increase self-esteem in women, as well as to create awareness around domestic violence and its prevention. The creation and assimilation of a participatory planning process made it possible to appeal to the use, identification and promotion of local resources, to organize actions, and to reduce the negative effects of arbitrariness in decision-making through prioritization and organizing of actions and interventions in the neighbourhood with a long-term vision in mind. Strategic community planning. A tool to guarantee local cohesion Since the beginning, around 1990, the Talleres identified the need for planning to find solutions to problems. However, as a result of the disenchantment derived from the ongoing Special Period, they struggled to engage actors, create a plan and materialize actions. At the time, the TTIB were the only planners at the local level. It wasn't until 1996 that a strategic community planning method was systematized and adopted, as an essential tool for running the Talleres, advising local government and responding to needs, through the mobilization of resources and community participation. The strategic plan for the City of La Habana, started in 1994, using a community-based methodology that aimed at including the local results into a provincial plan. Aside from promoting integrated planning at the municipal level, the methodology is in line with style and action of the Talleres.

Participants at TTIB's workshop on women's self esteem during an anti-violence event in the Atares neighbourhood. To prepare the community and the institutions for this innovative and unique planning method for urban contexts in Cuba, members of municipal governments, Popular Councils and TTIB teams had to go through a joint capacitation process that integrated their distinct visions and shaped a team work dynamic around the present and the future of the barrios. Beyond usual practice, the Popular Councils8 collaborating with the TTIB managed to present their planning to the Municipal Board of Directors9, thus facilitating a comprehensive knowledge exchange on the territory and a commitment to action at the municipal level, comprising rules for future monitoring of plan compliance. In spite of the limited financial and material resources at municipal level, that could only guarantee the realization of social actions, the planning process prepared the governments, the Popular Councils and their delegates to think and act strategically, switching from the traditional emergency-based, sectorial thinking to a more integrated thought process. Introducing agreed actions into annual economic plans was achieved only in rare cases, however; introducing these priorities in the budgets at local, provincial and national levels, and thus safeguarding their future implementation has yet to be achieved. However, this obstacle did not prevent many of these planned actions from becoming realized. Another positive outcome was that community planning resulted in participatory diagnosis, matching community needs with public priorities and an organizational capacity. Thus many projects identified through this process were funded through international cooperation bodies. Since their launch in 1994, the TTIB was able to generate investments through their planning, leading to the creation of new housing, small infrastructure works, improvement of public spaces, and services to the most disadvantaged communities.

The TTIB in La Guinera works towards the visual identification of its Community Centre. Neither the annual economic plans nor the joint projects have really created opportunities to develop a local economy, in the sense of creating businesses and local employment, in spite of these being identified as objectives in the territorial planning process to support the production of goods, local tourism and services. A lack of legislation, mechanisms and facilities persists, limiting potential future results. In fact, one of the strategies proposed in the planning process was to develop the local economy, which would have far reaching returns in terms of bringing in new financial resources for the City and the community, while delivering those improvements needed and increasing the positive impact. Even if the local economy has not been developed as much as hoped, the TTIB have been pushing toward local development by creating capacity, ensuring a vision for the future and supporting ways to obtain that vision, while contributing to the creation of community networks, promoting plan-based actions, mobilizing resources and offering credibility around the generation of mutual benefits. This whole process required breaking barriers, involving the marginalized and prioritizing their issues, reinforcing team work, systematizing actions and creating meaningful impacts in the barrios. Lessons learned After much time spent implementing these community planning processes, an evaluation is now possible. The following lessons have been learned from this experience. Hopefully they can be adapted and transferred to other contexts with similarly positive results:

|

* Rosa Oliveras GómezGómez, psychologist, works for the Group for Integral Development of the Capital (Grupo para el Desarrollo Integral de la Capital - GDIC), and is active member of the Latin American Network "Tecnologías Sociales para la Producción Social del Hábitat", affiliated to the Programa de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED). ° Translated from the original article by Mareike Brunelli. |

Universitas Forum, Vol. 5, No. 2, April 2015

|

Universitas Forum is produced by the Universitas Programme of the KIP International School (Knowledge, Innovations, Policies and Territorial Practices for the UN Millennium Platform).

Site Manager: Archimede Informatica - SocietĂ Cooperativa

Â